Unusual Humor of Russian Investigative Journalist Leads to Imprisonment

Serghey Reznik is the kind of reporter who would call a female judge a crocodile or quip that a prosecutor was nothing more than a tractor driver.

He intentionally humiliated sources, Nadezda Azhgikhina, executive secretary of the Russian Union of Journalists, told Capital News Service, “joking on their weaknesses or their not-so-nice appearance.” Some journalists’ union members didn’t like him.

Shortly after expressing interest in joining the union during the summer of 2013, Reznik was jailed for, among other things, insulting a state official on his popular LiveJournal blog.

On Nov. 26, 2013, he was sentenced to 18 months in a prison colony, which was then increased to three years in January 2015 after new charges were filed.

About a year later, while he was serving time at the No. 1 Detention Center in Russia’s Rostov region, the union granted Reznik his membership card.

“The fact that Reznik is a disgusting person doesn’t mean he was dangerous to society, that he should be detained and excluded from society,” Azhgikhina said. “The fact that he is in jail, everyone understands is a violation and is very unfair. It was fake – a fake case.”

During the same trial in which he was found guilty of insulting a public figure, Reznik was also tried for bribing a car mechanic to pass inspection and reporting false harassment threats to the police.

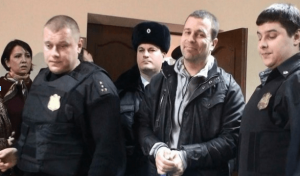

Russian journalist Serghey Reznik, 40, walks out of court in handcuffs. Credit: Reznik’s LiveJournal

In response to questions about his conviction from CNS, Reznik maintained his humor, writing that when he heard his sentence, he “realized that my success is recognized at the national level.”

Azhgikhina, who is also vice president of the European Federation of Journalists, said his case highlights the misuse of the judicial system in Russia to silence government critics.

“He will be in jail until he will agree to the rules of the game,” a former Russian television correspondent, who requested anonymity because he works in the government, said in an interview. “The rules are simple. If you are a journalist, you should cover officials only in positive way.”

<strong>‘A Trojan Horse’</strong>

The judge asked Reznik to introduce himself before the packed courtroom.

“Reznik, Serghey: Repressed,” he answered.

Reznik is well-known for his investigations of corruption among senior government officials and local law enforcement.

These investigations are the real reason he was brought before the court, according to many non-profit media advocacy groups, including the Committee to Protect Journalists and the International Federation of Journalists, which have denounced his sentence.

“He was successful in spreading information on some violations of law in Rostov region,” said Sergey Davidis, head of political prisoner advocacy for the Human Rights Center “Memorial” in Moscow. “They didn’t like it, and they tried to shut him up.”

Reznik often published stories exposing corruption in the Rostov police force, which is considered to be among the worst in the country. In Russia, about 45 percent of crimes go unsolved, President Vladimir Putin said in 2013.

“Catastrophic staffing problems are found every day in the ranks of the (Rostov-on-Don) police,” Reznik wrote in a 2013 article. “The question arises … are all these people qualified?”

Rostov Governor Vasily Golubev was another one of Reznik’s targets. When the governor took steps to privatize the regional energy industry, Reznik wrote the headline: “The criminal energy or ‘pension fund’ of Governor Golubev?”

The charges against Reznik are “incomprehensible,” according to Reporters Without Borders, which has closely monitored the case.

Prosecutors said Reznik bribed a technical assistant at the Fomina Auto Repair Shop with 2,000 rubles – about $45 – in exchange for letting Reznik drive off in his Hyundai Elantra XD without a vehicle inspection.

“I’m absolutely sure there are no similar crime charges in all of Russia,” said Davidis, whose organization named Reznik one of more than 80 political prisoners in Russia. “Nobody is interested in catching and prosecuting such so-called criminals.”

The court also charged him with reporting false threats to police. Reznik and his wife reported to the police that they received a slew of threatening calls warning the journalist to stop publishing articles. The state asserted that the threats were made by Reznik’s friends at his request, and accused Reznik of trying to draw attention to himself.

“I still don’t know how that all got turned around on us,” his wife, Nataliya, said in an interview with CNS.

Her bewilderment was compounded on a cold October night in 2012 when Reznik was attacked around 10 p.m. outside their apartment complex. Two men armed with a gun and a baseball bat sent the now 40-year-old to the hospital with injuries to his head, neck and back.

“It’s a joke really,” Galina Arapova, director of Mass Media Defence Centre and one of the lawyers on Reznik’s case, said in an interview. “(Reznik) was beaten up seriously … and they believe he organized it himself … That’s just nonsense.”

The final charge came under Article 319 of the Criminal Code: publicly insulting a representative of authority.

Arapova describes his case as a Trojan Horse. The first two “absurd” charges served as a way to bring Reznik into court and assign him the hefty jail time that the last charge alone wouldn’t carry.

“What they do is initiate some simple criminal case, and then something else, and only then do they bring out ‘insult public officials’ and then unite all the charges,” she said.

A crass written submission to the court, in which Reznik defends his innocence on the bribery charges, brought the additional 18 months on – a second charge of insulting a public official and false reporting of a crime.

“He wrote that – he is a very emotional and impulsive person – if that policeman saw me giving money to the director of the car business, maybe I saw him being involved with sexual activity with a school boy,” Arapova recalled.

People have continued to post on Reznik’s blog since his arrest, often with updates on his case, although the government can block access to LiveJournal.

In 2014, Moscow enacted legislation allowing censors “to cut off public access to online sources suspected of extremism without a court sanction,” according to the State Department’s 2014 Human Rights Report on Russia.

The Federal Service for Oversight of Communication and Information Technology used the law that February to temporarily block LiveJournal, the State Department said in its report.

Despite that threat, one blogger posted a picture of Reznik, smirking in a leather jacket, as he was led out of the courtroom in handcuffs.

“He wrote about what is happening in the Rostov region, where they think they know everything, but are afraid to say! He was a fearless journalist who ridiculed our vicious and rotten power until the very last days!” one user, y_shatalov, posted. “He continues to make fun of all the pettiness of the system, showing her that she is rotten!”

<strong>‘There is no man, there is no problem’</strong>

Reznik’s imprisonment reflects a larger strategy by Russian President Vladimir Putin to eliminate criticism of his government. Press freedom is the “main target of Putin’s regime,” said Vladimir Kara-Murza, a former journalist and coordinator of the pro-democracy Open Russia party in Moscow.

Since 1992, some 56 journalists have been killed in Russia, according to data compiled by the Committee to Protect Journalists. Thirty-eight were killed since 2000, the year Putin was elected president and instituted a crackdown on freedom of expression.

“Stalin’s infamous saying, ‘There is no man, there is no problem,’ is still relevant to many people here,” Kara-Murza, who recovered in the United States after being poisoned in Moscow, said in an interview with CNS. He alleges someone within the government was behind the attack, which left the otherwise healthy 33-year-old in a coma for three weeks.

The Glasnost Defense Fund, which works to defend freedom of expression in Russia, said that in 2014 alone five Russian journalists were killed, 52 attacked, 107 detained, 200 prosecuted, 29 threatened and 15 fired for politically motivated reasons.

In the Rostov region, a heavily industrial area bordering Ukraine, at least three journalists have been killed since 2002, two of them in Reznik’s city of Rostov-on-Don.

Natalya Skryl, a business reporter for Rostov-on-Don’s Nashe Vremya newspaper, died from head injuries in 2002. She was attacked outside her home at night, and hit on the head “about a dozen times with a heavy, blunt object,” according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Skryl had been investigating an “ongoing struggle for the control of Tagmet, a local metallurgical plant,” CPJ reported. She had recently obtained “sensitive information” about the story, the group said, which she planned to include in her story.

Vyacheslav Yaroshenko, the editor of Rostov-on-Don’s newspaper Korruptsiya i Prestupnost, died in 2009 after he “was found unconscious with a head wound in the entrance to his apartment building early in the morning,” according to CPJ.

The motive in his death is still unconfirmed, although his colleagues believe he was killed in retaliation for publishing stories about corruption within the Rostov law enforcement, CPJ reported. His publication’s name translates to “Corruption and Crime.”

In October 2012, Reznik also was attacked late at night outside his apartment complex. Two masked men – one armed with a baseball bat; the other with a gun – beat him. He was covered in red welts and hospitalized.

His wife was with him that night. She said he was clearly targeted.

“They didn’t attack me, they only attacked him,” said Nataliya. “I was standing next to him and they didn’t touch me.”

During his trial the following year, the prosecution said the two attackers were Reznik’s friends and that he had paid them to attack him to bring more attention to his work.

“The police did not search for the attackers,” Reznik wrote CNS from prison. “After all, it is the hardest to look for yourself.”

Russia ranks 10th on CPJ’s 2015 Global Impunity Index, which highlights countries where journalists are killed and their murderers go free.

“Regrettably, impunity for the murder of other journalists in Russia … contributes to a climate of fear and self-censorship and puts journalists’ safety at risk,” Daniel Baer, the U.S. Ambassador to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, said Nov. 5 at the OSCE Permanent Council in Vienna.

It takes “real courage” to be a journalist in Russia, Kara-Murza said.

“Journalists are being imprisoned, journalists are being threatened and too many journalists are being killed,” he said.

CPJ lists Reznik as the only imprisoned Russian journalist, though Russian media outlets have covered the case of another man from Rostov-on-Don.

Aleksandr Tolmachev, the editor of the magazine Upolnomochen Zayavit and the newspaper Pro Rostov, has been imprisoned since 2011 for extortion. In 2014, the seriously ill man was sentenced to nine years in a penal colony.

“The climate now is that everyone started to fear,” Reznik wrote from prison. “Naturally, many hands went down.”

It is not just journalists who feel pressure in Rostov, located nearly 600 miles from Moscow.

“There are some regions where there is more freedom and there are some tough regions,” said Memorial’s Davidis. “Rostov (is) a very tough region. It’s very difficult to oppose authorities there and it concerns not only journalists, but all opposition and activism. They have a lot of ways to fabricate reasons for criminal prosecution and they do it.”

Boris Batyy, a coordinator of the liberal “Solidarity” movement in Rostov-on-Don, was arrested after protesting Russia’s military actions in Ukraine, which borders the Rostov region, with a sign that said, “Putin, stop your lying and fighting!”

In November 2014, he was prosecuted for insulting police and publicly calling for extremism, according to The Caucasian Knot, a Russian news organization that covers politics and human rights. Batty says neither charge is the real reason he was arrested.

“One of the reasons political police put attention on me is because I made some comments on the posts about Serghey Reznik’s trial,” Batyy, who is seeking political asylum in Germany, said in an interview with CNS.

“I attended about 70 percent of his court hearings and I saw the lying, I saw the false trials,” he said. “There was just one aim: to deal with him.”

Authorities in such a remote region face little scrutiny in Russia or elsewhere, said journalists.

“Independent activities in the regions are harshly persecuted – I mean prosecuted, though those are the same things now. That’s especially true in the south,” Kara-Murza said. “Outside of Moscow and St. Petersburg it’s much more difficult for independent media, opposition politicians and civic activists to function, to live.”

<strong>‘Small islands of press freedom’</strong>

Through their television screens, the Russian people have been told that Kiev is under Nazi control; that there are no Russian forces in Ukraine; that the United States has deployed combat dolphins to the Black Sea to undermine the Russian government.

The Russian government or state-controlled companies own more than 60 percent of the country’s 45,000 registered local newspapers and periodicals, according to the U.S. State Department’s 2015 Human Rights Report on Russia. All six national television channels and 66 percent of the 2,500 television stations are completely or partially government owned, it said.

On July 21, 2014, Putin signed a law forbidding many non-state owned television companies from funding themselves through advertising.

Many newspapers have agreed, through “support contracts,” to provide positive coverage of government officials and policies in exchange for financial security. About 90 percent of print media relied on the state for printing, paper and distribution, according to the latest State Department report.

“We only have small islands of press freedom now,” Kara-Murza said. “Of course, the Internet is still free, thank God.”

But even on the web, there’s been a crackdown. From 2012 to 2013 the number of criminal proceedings against Russian bloggers doubled. It was during a period known as the “Snow Revolution,” where large-scale anti-Putin protests questioned the 2012 election’s legitimacy.

The Agora human rights group in Russia reported 226 criminal cases against registered Internet users in 2013, compared with 103 such cases in 2012.

The Russian media challenges “the very notion of balanced, fact-based reporting,” said Daniel Calingaert, the executive vice president of Washington-based Freedom House.

The United States, he believes, should try to change that.

The United States should provide “legitimate news coverage for countries who don’t have it,” Calingaert said. He said the United States should fund Russian-produced independent media and a Russian version of the nonprofit ProPublica online publication, which conducts investigative reporting.

Last January, a law restricting foreign ownership of media outlets to no more than 20 percent went into effect, according to the State Department’s latest report.

“Corruption is very widespread and goes to the highest levels of the Russian government,” he said. “There’s probably a lot that can be exposed that isn’t being exposed.”

In April, The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists found that as much as $2 billion had been secretly passed to banks and offshore companies linked to Putin’s confidants.

Novaya Gazeta participated in the global investigation. After its story was published, tax authorities began an investigation into whether any foreign grants were used for the project. Since 2000, five Novaya Gazeta reporters have been killed, according to CPJ.

Russian propaganda does not just affect Russian audiences but has repercussions on international relations, Calingaert said.

Since Russia invaded Ukraine, more than one-third of the airtime on Russia’s main official television channel has been devoted to Russia’s version of the intervention: Nazi occupation. No Russian forces. Secret U.S. dolphins.

“Russians bombarded for years with propaganda don’t have a clear picture of what’s really happening in the world or in their own country,” he said. “It makes it that much easier for their government to manipulate public opinion and to pursue policies dangerous to its country and its neighbors.”

Tom Malinowski, assistant secretary of the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, discussed the issue at the United Nations in 2014.

“When media loyal to the Russian state relentlessly broadcasts such propaganda and Russian authorities shut down alternative sources of information, more and more people are lulled into thinking that black is white, up is down, and two plus two may equal five,” Malinowski said.

<strong>Groundhog Day</strong>

Reznik compares himself to Bruce Willis; close-cropped brown hair and a light stubble, “but I don’t shave my head,” he wrote to CNS.

He also draws on American pop culture to explain his life in prison.

“There is a wonderful American movie ‘Groundhog Day,’” he wrote from prison. “Lifting, breakfast, news, chat with the prisoners, books … so the days pass.”

For his wife, days are filled with worry. She knows her husband is an optimist but wonders whether the prison is worse than he lets on. He jokes with her that conditions are better than the summer camp he endured as a young boy.

“It is harder for me than it is for him,” she said. “He is strong, he is capable, he is resilient.”

Every two months the couple gets to speak through plexiglass. Every three months she can stay in prison with him for three days. Each time, he asks her to bring him newspapers.

Nataliya, a yoga instructor, communicates frequently with his lawyers, who are working to appeal. They plan to take his case to European Court of Human Rights, said his lawyer Tumas Misakyan.

“Why is he so dangerous, and why is he being eliminated in Rostov as a journalist? Misakyan said in an interview. “Because he wasn’t afraid to write.”

Once he is released from prison in October 2016, his sentence stipulates, he cannot practice journalism for two years. For Reznik, the restriction is a point of pride.

In 20 years, he wrote from prison, he has heard of only one other journalist who irritated the government enough to warrant such a prohibition.

“I find it unfair,” Reznik wrote, “that our names are not listed in the Guinness Book of Records.”

Campaign

About this Site

Pressuncuffed.org seeks to encourage and promote rigorous student reporting, scholarly research and debate on the role of, and obstacles to, independent journalism in the United States and abroad. Our website features reporting by University of Maryland students about press freedom in the United States and abroad. It also offers resources to instructors elsewhere who may want to teach classes or hold workshops on this theme. In the near future, this site will become a place for student work from around the country and abroad.

Dana Priest, two-time Pulitzer Prize winner at The Washington Post and Knight Chair in Public Affairs Journalism at the University of Maryland.