18 Years Without A Father

SPOKANE, Wa.-Baby Lea breaks a toothless smile as her grandmother whispers sweet Russian words into her ear. Her big brother Aron runs into the room and gives his sister a kiss. “Manyunya,” he calls her; Russian for “little one.” His father yells for him to clean up his toys. The aunts giggle at the toddler’s antics.

In the kitchen of their cozy home here, a family seems complete.

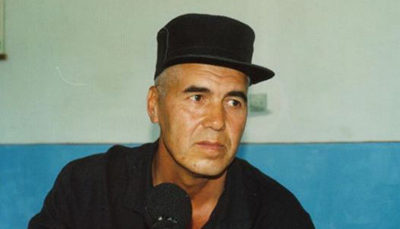

But they are missing one man: their father, grandfather, husband. He’s been gone 18 years. The only evidence he ever even existed is a single fading photograph, taped on the refrigerator.

The last time Muhammad Bekjanov saw his youngest daughter, she was five. Now she’s 22. “When a person dies, you have a chance to mourn and finally move on,” said Bekjanov’s oldest daughter, Aygul Bekjan, 37. “There is never closure in sight when someone so close and dear to you has to suffer…”

Bekjanov spent the better years of his life sitting in a series of underground cells, facing solitary confinement and brutal torture which at times left him paralyzed. He has missed family milestones including graduations, a wedding, and the birth of his two grandchildren. As one of the longest imprisoned journalists in the world, he has finally been released after 18 years.

There was a time, though, that Bekjanov and his family thought he would never be released.

Muhammad Bekjanov was 45 and the editor of an exiled opposition party newspaper when Uzbek authorities decided he was a terrorist. He is now 63. Until his release, he and his colleague, Yusuf Ruzimuradoz, who is still imprisoned, were the longest imprisoned journalists in the world.

He has been in a series of dark underground cells for so long that the pro-democracy party he once advocated for now consists of a dozen old men, all in exile.

But other things haven’t changed in Uzbekistan. Though the late heavy-handed authoritarian, Islam Karimov no longer rules, a million people are still forced to labor in cotton fields. The United Nations still calls its prisons halls of torture. Independent media are still banned. Dissent is still crushed.

The U.S. government still considers Uzbekistan an ally.

The situation in the largest Central Asian country has only gotten worse since Bekjanov’s conviction in 1999. The State Department estimates there are over one million people subject to forced labor. Thousands of civil and political activists are in prison according to Human Rights Watch-more than all former Soviet nations combined.

Bekjanov was no stranger to this harsh climate. As editor of the opposition newspaper, Erk, a publication of the Erk party, his was the leading voice for democracy after the fall of the Soviet Union. Bekjanov’s brother, Muhammad Salih, was party leader and posed the only real political threat to Karimov’s rule.

Through Erk, Bekjanov reported on labor abuse in the cotton industry, Uzbekistan’s largest export, as well as child labor, women’s rights, forced sterilization of women, and other issues the government tried to hide.

“People actually came to their office because it was the only newspaper that was writing the truth and they complained about what was happening, so it really was the voice of the people,” said Nina, Bekjanov’s wife.

The Erk party was banned in 1994 and authorities began threatening Bekjanov and his reporters. To continue publishing, he moved to Turkey and secretly sent articles back to Uzbekistan.

His family, however, was followed by government authorities. Their telephones were tapped and they received written threats from the authorities. “We had two people sitting by the entrance to our apartment all the time. I would go to school and I would have two humongous guys following me back and forth,” said Aygul Bekjan.

They installed a thick metal door to protect themselves against police. When they would come to raid that house, “We would call all the neighbors, get everybody up,” said Aygul, “They would come out with their big spoons and sticks whatever they could bring just to protect us. And it was normal.”

Eventually, authorities ransacked their property, shut down their bank accounts and confiscated their apartment. By then they had also taken everything they believed to be evidence against Bekjanov, copies of articles, “even our pictures, private things, letters that we had in our apartment…we were just left with nothing,” said Nina, except the one photograph.

Since Nina held Ukrainian citizenship, she decided to move the family there. But she had no passports, no documentation, nothing but a few bags. She was also seven months pregnant with her third child.

Wearing light spring dresses, she and her two young daughters walked across the northern border into the frigid winds of Kazakhstan. Then they took a bus to snowy Astana.

“When we got to Kazakhstan we got a hotel room. I fell on top of a heater in the hall,” said Nina. “We were so cold. I fell on top of the heater and it felt so nice and warm, at that point I realized that I didn’t want to go anywhere else, I just wanted to stay there forever.”

From Kazakhstan, they flew to Moscow, and then to Kiev. Her husband met them there. For five years, he worked in a small store and continued his newspaper work in secret.

“He was very fun, always joking around,” said Aygul. “He was the one who spoiled us, mom was always strict. If you wanted to buy something you went to your dad.”

His children also remember a man ahead of his time. He wrote about women’s equality and wanted his daughters to be well educated.

This time of limbo in between safety and reality, ended one days when Aygul came home to find their new apartment ransacked, the doors open and her father gone.

Days later they learned Bekjanov had been arrested by Ukrainian police at the request of the Uzbek government, and had been extradited home.

The U.S. Embassy quickly granted the family refugee status and helped find them a place to live in the United States after they convinced Nina it would be more effective to advocate for her husband’s release from there.

* * *

The timing of Bekjanov’s arrest coincided with the run-up to the 2000 election and the imprisonment of tens of thousands of dissidents. Bekjanov and his colleague Yusuf Ruzimuradov were accused of a series of Tashkent bombings.

In the six months leading up to his trial, Bekjanov told his wife he was brutally tortured in the basement of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in Tashkent. For five days he laid paralyzed, in a pool of blood and pus, unable to move, surrounded by the screams of other prisoners.

At one point he heard heavy footsteps, then a gruff voice: “Oh wow, how lucky, you have lived.”

“They just throw you in and wait for you either to die, or to survive, you know it’s kind of a game for them to see what’s going to happen,” Bekjanov told his wife during one of her rare visits.

The tortured erased some of his memory, Bekjanov told her. It took him two months to remember his childrens’ names.

At his trial Bekjanov said he was forced to incriminate himself and other tortured witnesses testified against him to save their own lives. He was charged with “…such serious offenses as possession of firearms, explosive substances and explosives; forgery and use of stamps and documents; illegal organization of criminal groups; encroaching on constitutional order of the Republic of Uzbekistan, etc,” according to a letter from Uzbekistan.

The Tashkent Regional Court found him guilty and imposed a 15 year sentence.

He was then transferred to Jaslyk prison, where he spent the first three months in solitary confinement. He told his wife he found companionship with the bugs that littered his cell floor. The movement of the spiders stretching their way across the icy concrete gave him hope. The scuttle of their small black legs brought life into his world, as did the tinted light from a dusty window.

“The little bit of light, the little window there kind of gives you hope,” Bekjanov told Nina, when she visited him five years after his initial arrest.

Human rights groups refer to Jaslyk as a concentration camp. Set up in 1999 on the site of a former Soviet-era chemical weapons testing area in northwest Uzbekistan, an area known for its deadly cold winters and exceedingly hot summers, it is now home to many political and religious activists.

The prison currently houses 5,000 to 7,000 inmates, according to Human Rights Watch.

Bekjanov told his wife he was beaten every day in Jaslyk, where he spent several months. He lost hearing in his right ear. One of his legs was broken but never treated. After he contracted tuberculosis, the international outcry forced authorities to transfer him to a Tashkent prison hospital where he was treated for three months.

He was then transferred to two other prisons: Kagan in Bukhara and Kasan in Kashkadar’ya. Bekjanov told his wife that he only remembered each by how much he was tortured.

* * *

In March of 2012, the month of Bekjanov’s announced release, Nina traveled to Uzbekistan to collect him. Though his original release was to be the summer of 2014, he had received partial amnesty in September 2003 and his sentence was reduced by 1/5 to about 12 years and eight months.

Authorities told Nina to wait, they would bring her husband to her. But they never came. For three months she stayed in Tashkent. Then authorities told her to go home and wait for a letter. The letter never came either.

Instead she learned from the U.S. Embassy that five years had been added to Bekjanov’s sentence.

She later received an explanation from Uzbekistan’s delegation at the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s (OSCE) Permanent Council. It said:

“While serving his sentence, inmate M. Bekjonov had systematically violated internal regulations of the correctional facility, did not obey legitimate demands of the prison administration, and for the entire stay in the colony was disciplined nine times, four of which times took place in 2011.”

A criminal case on the disobedience charge had been opened in October 2011. After the additional sentence was added, Bekjanov was transferred to Zarafshan prison, where he serves the rest of his time.

Bekjanov’s extended sentence is not an exception, but the norm. Thousands charged with terrorism and extremism between 1997 and 1999 have been given additional prison sentences at the eight to nine year mark, said Steve Swerdlow, Central Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch.

“It’s one of those unique features of Uzbekistan which makes it really cruel,” said Swerdlow. “You go in, and you never come out.”

* * *

At the gates of the Zarafshan prison, a sea of gray infrastructure and guards with rough unsmiling faces greeted Nina Bekjanova as she entered. Clasped to her side was the plain black clothing she brought for her husband, stripped of their brand tags, as required.

In her other hand, a dark grease spot spread through the bottom of her paper bag, as honey and fat melted off the dried meat she had fried for her husband, now almost 13 years into his sentence. The fat made the food stay good longer, and it stuck to his thin, tall frame. At 6’1 he weighed a mere 110 pounds.

For three days Nina was permitted to live with her husband in a small barrack with two beds and a communal kitchen, she said. But they were never truly alone.

“You feel the pressure all the time,” said Nina, “You know that they are always listening to you and watching you.”

Bekjanov and his wife could only exchange whispered snippets in a short alleyway where sometimes, there were no guards.

The prison limits visits to two three-day visits a year.

For those three days, Bekjanov read all of the letters and studied the photos his wife brought of his family in the United States. At the end of the visit, he tearfully returned them, fearful they would be confiscated otherwise.

“I would ask him questions but he would never tell me what was happening inside of the prison, possibly because our every word and step was being watched,” said Nina.

“When I came to visit him at the beginning of his jail sentence, he would come off as incredibly energetic and brave. With time, however, he began to look worse and worse as his jail sentence dragged on. Especially after he was given five more years. Before that, there was still resemblance of what he used to be. But after that, I didn’t recognize him.”

While Bekjanov sat in prison, the government was cracking down even harder on dissidents after the Andijan massacre in 2005. Citizens peacefully protesting poor living conditions and government corruption in Andijan, five hours east of Tashkent, had been shot by police who opened fire on the crowd killing hundreds of men, women and children.

In the years following the massacre, the Uzbek government further restricted civil society and harassed anyone believed to have either participated in or witnessed the events, according to human rights groups.

It also forced the closure of international organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and independent media outlets through a mandated re-registration process, which enacted stricter regulations.

There are 663 approved newspapers in Uzbekistan, 35 radio stations and 53 television stations, according to the government. Most broadcasting comes from four state-run television channels.

“The expectation was that I would be the mouthpiece of the government,” said Navbahor Imamova, a former reporter at the Uzbek state radio. Imamova now a journalist at the Voice of America in Washington D.C., says her script was censored every day before going on the air.

Journalists report only state propaganda and cannot safely cover sensitive issues, said Alisher Siddique, Uzbek Director for Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty (RFERL), a U.S. funded broadcast outlet in 23 countries where an independent media is banned or struggling.

RFERL was one of the many publications kicked out of the country after the Andijan crackdown.

“Believe me, the Uzbek government thinks the list of sensitive issues is very big,” said Siddiq. “Even while you are covering football, or being critical of Uzbek’s football team, you be careful that you don’t connect it to the government, to the lack of funding or anything like that. The government…cannot be involved.”

Publicly insulting the president is a crime punishable by up to five years in prison in Uzbekistan. The Embassy of Uzbekistan declined to comment for this article.

* * *

Uzbekistan is party to some of the most important U.N. declarations on Human Rights and its laws prohibit torture. The constitution includes provisions protecting some of the most important foundations for a democracy.

Yet its record of abuse is long and well-established. “The use of torture in Uzbekistan is comparable to that used during the Stalinist era, when confession was sufficient grounds for conviction,” a UN human rights committee found in 2010. “In order to obtain such results, investigating officers routinely use the most brutal methods of torture to exert pain, humiliation, and moral suffering.”

Since 2008, the European Court of Human Rights declared in several cases that extraditing people to Uzbekistan would violate the Convention Against Torture, which prohibits the transfer of anyone to a country where they would likely face a serious risk of being torture.

The International Committee of the Red Cross, an organization that visits prisoners and works to prevent abuse and improve penal conditions, was forced to terminate visits to detainees in Uzbekistan in 2013. “We are unable to follow our standard working procedures when we visit detainees to assess the conditions in which they are being held and the treatment they are receiving,” said Yves Daccord, director-general of the ICRC in an announcement. Visits had become pointless, he said.

U.S. policy toward Uzbekistan largely has been driven by military and intelligence needs. The CIA used an old Russian airbase there as a staging area for its decade-long hunt for Osama Bin Laden.

“When I was there we were running drones out of an airbase trying to get Osama Bin Laden,” said Joseph Presel, former U.S. Ambassador to Uzbekistan. “And the Uzbek’s would let us do it. But it’s kind of hard to say we want some really serious help here, thank you very much, and by the way stop being shits about journalists.”

The United States also enlisted Uzbekistan’s cooperation in the Northern Distribution Network, a military supply route to landlocked Afghanistan. Its cooperation gave Tashkent leverage over the United States, said Swerdlow.

In 2011, former president Karimov threatened to suspend the transit of goods through the NDN, when then-US secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, presented a Women of Courage award to Mutabar Tadjibayeva, a released Uzbek human rights campaigner.

Concerns about the Taliban resurgence and ISIS recruitment in Afghanistan have also spurred increased U.S. involvement in the region.

The State Department has said its Uzbekistan programs support the strengthening of democracy, human rights and rule of law, as they seek to reduce torture and improve treatment of citizens.

International human rights groups call for targeted sanctions, a ban on visas to Uzbek officials and freezing assets.

“There’s an argument to be made that bitching and moaning and yelling and screaming and jumping up and down has an affect and sometimes it does,” said Presel. “But by and large if what you’re trying to do is get [someone] out of prison and out of the country, the way to do that is to keep your mouth shut. And to ask [them] to keep their mouth shut when they get out at least for a while. Because we may be trying to do a deal for [them] and four others…”

In 2011, President Obama congratulated Karimov on 20 years of independence, and the two leaders pledged to increase cooperation. Obama said a more prosperous and secure Uzbekistan would benefit both countries.

“I like to say, in the case of the Uzbeks, that you can quite often get the Uzbeks to do things. You can even get the Uzbeks to do things they don’t want to do once in a while,” said Presel, “And the way to do that is like porcupines making love- slowly, very very carefully.”

In 2015, then-Secretary John Kerry made a visit to Uzbekistan to meet with the five central Asian countries. Though the words “human rights” were not uttered publicly, Karimov released Murod Juraev, 63, one of the world’s longest serving political prisoners just ten days later. He had served 21 years, nearly double his original sentence.

Like Bekjanov, Juraev was an active member of the Erk Party, who was arrested in Kazakhstan and extradited to Uzbekistan. He was charged with attempting to overthrow the government.

The Erk party had previously been the only real political challenge to Karimov, said Swerdlow. But no longer. It is now considered a defunct collection of old opposition members living in exile. Erk has no influence and little recognition with young Uzbeks today, according to experts.

“The Erk party exists almost in name only,” Swerdlow said. “Some of its individual members continue to be activists and reach out to the population and some of them have been imprisoned…but were talking about people you can count on one hand or two hands at the most.”

Karimov ruled for nearly three decades, despite the legal two-term limit. International watchdogs said elections where Karimov sometimes won 90 percent of the votes, were shams.

Though free, Bekjanov cannot yet return to the United States as his passport request is being reviewed by the Uzbek foreign ministry.

His daughter Aygul says she thinks about him every day. Her son Aron was born on her father’s 56 birthday. “I was one week overdue, I think it was just a gift waiting to happen for him,” said Aygul.

Aron, now seven years old, asks frequently about the grandfather he has never met but hears a lot about.

Aron used to ask, ‘Can we just go and have some superhero get him out of there?’ said Aygul, “because he thinks bandits took him, and well, they are bandits.”

Campaign

About this Site

Pressuncuffed.org seeks to encourage and promote rigorous student reporting, scholarly research and debate on the role of, and obstacles to, independent journalism in the United States and abroad. Our website features reporting by University of Maryland students about press freedom in the United States and abroad. It also offers resources to instructors elsewhere who may want to teach classes or hold workshops on this theme. In the near future, this site will become a place for student work from around the country and abroad.

Dana Priest, two-time Pulitzer Prize winner at The Washington Post and Knight Chair in Public Affairs Journalism at the University of Maryland.