Ukrainian Journalist Lured to Moscow, Arrested

Ukrainian journalist Roman Sushchenko wasn’t reporting in Moscow when the Russian secret police arrested him there. A friend of 20 years lured him from his home in Paris so Russia’s intelligence agency, the FSB, could arrest him, said his lawyer, Mark Feygin.

For the past ten months Sushchenko has been held in Lefortovo, a Soviet-era prison known for its psychological abuse of prisoners, including dissident writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who exposed the horrors of his gulag interrogation during the Cold War.

Charged with spying for the Ukrainian Defense Ministry, Suschenko is a pawn in the larger conflict between Russia and Ukraine, say his lawyer and supporters.

“It’s all part of a campaign to make Russians fear for their lives, like all these Ukrainians are out to get them even though it’s actually Russia that’s invading Ukraine,” said Alya Shandra, managing editor at Euromaidan Press, an online English-language newspaper that also translates Ukrainian news and analysis in English. “It’s very sophisticated state propaganda.”

The Russian Embassy in Washington did not respond to requests for comment. But the FSB said in a statement shortly after his arrest that Sushchenko had been collecting information about Russian armed forces and was a member of the Main Intelligence Directorate of the Ukrainian Defense Ministry:

“The Ukrainian citizen was focused on gathering information containing state secrets about Russia’s armed forces and National Guard troops, the leak of which could have damaged the defense potential of the state,” the statement, broadcast on Russia 24 TV channel, read

The Ukrainian Defense Ministry issued a statement denying that he worked with them and Sushchenko denies the charges.

In fact, Sushchenko was a foreign correspondent in France for the Ukrainian publication Ukrinform at the time of his arrest. He wrote about the Russian-Ukrainian conflict from the international point of view, which may have caught Russia’s attention, Feygin said in an interview with CNS.

“He’s more than a journalist, he’s a Ukrainian journalist, and his problem is much bigger than he is…he’s in the middle of Russian-Ukrainian conflict,” he said. “That’s why his case is more important.”

Feygin is a widely known politician and lawyer who has represented members of the punk band Pussy Riot who were charged with hooliganism for performing a song critical of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Mark Feygin Meeting With the Ukrainian President

Feygin said he is regularly followed and his phone is tapped, but that he believes his fame protects him against investigators, the court and Russian authorities.

Before he was arrested, the FSB tracked Sushchenko, Feygin said. It tapped his phone during one of his previous trips to visit his family in Moscow. Feygin said this is not an unusual action by the government.

“It’s something ordinary that’s usually [done] by an investigation office in Russia,” Feygin said. “They already had a plan on how they would use his arrest.”

Sushchenko had been missing for three days, when a human rights activist and journalist, Zoya Svetova, found him by accident in the quarantine ward of Lefortovo Prison on Oct. 2, 2016.

THE CONFLICT IN UKRAINE

Second only to Russia, Ukraine was the most important economic component of the Soviet Union. The country gained independence in 1991 after the collapse of the Soviet Union and attempted to liberalize its economy.

There was pushback from within the government however and output fell to less than it was before independence. Ukraine grew dependent on external sources such as Russia for energy supplies. In 2009, the country’s economy contracted 15 percent. Because of this, it ceded certain privileges to Russia, such as use of its naval base in Crimea, which it traded for a gas discount in 2010.

Ukraine’s economy has been unsteady ever since, engaging in a trade war with Russia in 2015 that has reduced trade between the two countries. At the start of 2016, Ukraine entered a deal with the European Union that it hoped would open the economy and improve trade with European countries.

Cynthia Martin, head of the Russian studies department at the University of Maryland, said the conflict is anything but black and white. Some Americans, for example, can only see “Russia [as] the enemy, Russia [as] the aggressor, Russia [as] the Soviet Russia — and it’s not exactly true,” she said.

The economic ties between Russia and Ukraine run deep. Today, Ukraine is one of the largest importers of Russian natural gas and stands in as a strategic buffer between Russia and western Europe. It is also home to about 7.5 million ethnic Russians.

Russian military intervention in Ukraine began in 2014. The International Criminal Court said this invasion is a crime.

A FATHER AND AN ARTIST

Sushchenko’s son, 9

Sushchenko has two children waiting for his release: his daughter, 25, and his son, 9.

His son, Maxim, wrote to Putin recently to appeal for his father’s release:

“As it turns out, I am now the head of the family for my mother and sister, who are with me in Kiev,” he wrote, according to a copy of the letter obtained by CNS. “. . . Much of my father’s fate depends on you, and mine does too . . . I’m 9 years old and I can’t carry my family on my own. So help me.”

Sushchenko’s Daughter and Son

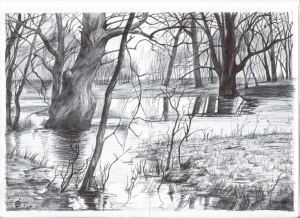

Sushchenko’s daughter Julia told CNS that her father “loved drawing since he was a kid. In his childhood and adolescence there were drawings in notebooks and notepads, now, it’s oil paintings. Many of his friends have at least one picture drawn by him,” she said, and there was an exhibition of his work in Kiev.

Drawing from Lefortovo, courtesy of Julia Sushchenko

He prefers to paint with colors, she said. Prison guard will allow him only a black pen.

In a letter to his colleagues at Ukrinform, Sushchenko told them he is not starving and is getting enough sleep. He keeps a diary that he plans to use as material for his book once he is freed.

He also has written a letter to the President of Ukraine, Petro Poroshenko: “I am storing [your letter] in a separate shelf in my jail cell right next to the letters from my loving wife, daughter, son, parents and my closest friend,” he wrote after Poroshenko wrote him after his arrest.

The letters are stamped with the Russian government seal, because Russian authorities read and check his mail, said his lawyer.

The journalist said the presence of these handwritten letters: “energizes my soul, helps my patience and raises my mood in a condition of utter isolation.”

ARRESTED IN A “COLD WAR-ERA MANNER”

Sushchenko was arrested in Moscow on Sept. 30, 2016. He was then charged with spying by the Russian Federation on Oct. 7.

Sushchenko’s arrest “was done in a very cold war-era manner,” said Gulnoza Said, the Europe and Central Asia research associate for the Committee to Protect Journalists, a nonprofit advocacy organization.

Shandra, the Euromaidan editor, who is also a member of the “Let My People Go” campaign, said Ukrainians were not surprised when he was arrested. “We’re pretty used to Ukrainians being kidnapped . . . it’s like, ‘oh no, another one.’” she said.

Feygin said he suspects there are other Ukrainians that the Russian government would like to arrest and hold hostage in exchange for Russian prisoners in Ukraine.

THE MEDIA IN RUSSIA & UKRAINE

Certain Russian media outlets are banned in Ukraine. However, Russia allegedly pays other, friendly media organizations to disseminate disinformation, according to reports published in Euromaidan Press based on the leaked emails of an aid to Vladimir Putin.

Among the leaked emails was a letter from Pavel Broyde, formerly a public relations professional in southern Ukraine, to the aid. It read:

“The experience of Crimea demonstrates how strong the factor of the presence of Russian TV channels and sympathy of local outlets to Russia, influences public opinion. ”

Another document forwarded contained specific sentences to be published by the Kremlin’s network of alleged media agents, such as: “Kyiv is trying to blame Putin personally” and “Constitutional amendments proposed by Poroshenko are a disguise for creating a dictatorial regime.”

The email also designated groups of influential people, including journalists, historians and political scientists, and placed them in groupings such as: “ineffective persons,” “averagely effective persons,” “highly effective persons,” and “status persons,” according to accounts in Euromaidan Press.

TIME IN PRISON

Sushchenko and his wife saw each other for the first time in almost half a year in an isolated room, separated by a pane of glass. During the two-hour visit, they pressed their hands together against the glass, the closest they’d gotten to touching in a long time, his wife, Anjela Sushchenko, told CNS.

She said she tried to avoid looking at the jail staff watching them, but it was difficult to ignore their presence. A guard informed them they could talk to each other through the phones on each side of the glass.

Sushchenko spends his days reading, drawing and writing in a 6×6 ft. room, his wife said. His jail diet consists of porridge, pasta, tea, bread and jelly. He is allowed to shower once a week.

In his cell, he has a small window through which air and a sliver of light can enter. His days are routine: he wakes up at 6 a.m., lights out is at 10 p.m. and, weather permitting, he is allowed one hour outside for walking.

Sometimes he draws scenes of nature to pass the time. Supporters have sent him more than 50 books, she said.

The last time she was allowed to visit, she said, he held himself with dignity.

“He comforted me and said that this misunderstanding would end and our family would be together again,” she said. “ . . . But, of course, we know…he does not get much sun and fresh air, and does not get the right vitamins.”

Campaign

About this Site

Pressuncuffed.org seeks to encourage and promote rigorous student reporting, scholarly research and debate on the role of, and obstacles to, independent journalism in the United States and abroad. Our website features reporting by University of Maryland students about press freedom in the United States and abroad. It also offers resources to instructors elsewhere who may want to teach classes or hold workshops on this theme. In the near future, this site will become a place for student work from around the country and abroad.

Dana Priest, two-time Pulitzer Prize winner at The Washington Post and Knight Chair in Public Affairs Journalism at the University of Maryland.