Living like a fugitive

![]()

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan – The most famous television journalist in Pakistan lives like a fugitive. Hamid Mir tells no one where he is going, how he will get there or where he will spend the night.

At Mir’s office, his curtains are always drawn. He uses at least two cellphones and, until recently, he rotated among three residences to obscure his precise location, even from friends.

Even with all these precautions, Mir is anxious and jittery, most of all when he gets into the back seat of his bulletproof car to drive to the television studios for his show, “Capital Talk.”

“Most nerve-racking part of the day,” says the 49-year-old father of two, clenching the grab bar above him on a recent morning as the driver careens through the city taking last-minute instructions on which roads to take. Mir ignores incoming calls from unknown numbers and swivels from side to side, watching traffic to see whether any vehicle stays too close for too long.

Mir is not just trying to avoid recognition; he also is desperately trying to avoid a repeat of what happened to him a little over a year ago as he was being driven from the airport to the Karachi offices of Geo Television, the network that employs him.

That day, a man standing along the road opened fire on his car.

When the first bullet shattered the rear passenger window and tore through his right shoulder, he actually felt relieved, he said. He was still alive.

But then he realized that four men on two motorcycles were chasing his car through the city streets, guns out.

Bullets pierced his body, including his right thigh, stomach and bladder. By the sixth impact, he began losing consciousness, and his mother, father, wife and children appeared.

“Their faces went around in my head,” he recalled.

The attack on Mir and the continuing death threats against him are emblematic of a broad backlash against transparency and independent journalism in many parts of the world.

Six out of seven citizens have little or no access to insightful reporting about their governments even though the Internet has made other types of information ubiquitous, according to organizations that monitor reporting internationally.

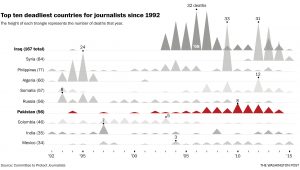

Worldwide, the last three years have been particularly hard on those who gather the news: An average of more than one journalist a week has been killed for reasons connected to his or her work, or about 205 journalists, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, a nonprofit organization that investigates attacks on the media.

This year, at least 38 more have been killed. The dead include eight Charlie Hebdo journalists in Paris, a Brazilian radio broadcaster tortured and shot, an Indian reporter burned to death for investigating local corruption and a Japanese freelance photographer who was beheaded by the Islamic State in Syria.

Pakistan, with its volatile mix of shadowy security forces, internecine political battles, terrorist groups and criminal networks, is one of the most dangerous countries for local journalists outside of war zones, according to the United Nations and press freedom groups. Since 2001, 52 journalists have been killed here because of their reporting. Criminal charges have led to convictions in only two cases.

Who nearly killed Hamid Mir on April 19, 2014, remains a mystery.

Click on the image to see the full interactive graphic

A magnet for hatred

To be a crusading journalist in Pakistan is to have many enemies.

In Mir’s case, some elements in the country’s most-feared intelligence agency, Inter- Services Intelligence, or ISI, despise him for his exposés of their double-dealings and secret influence on politics, he says. The Pakistani Taliban and local terrorist networks hate him for his outspoken criticism of their tactics and ideology and for his support of girls’ education. Various political parties revile him for finding corruption in their ranks and for his more tolerant view of India, which they would rather blame for Pakistan’s many ills.

The sunny view of press freedom in Pakistan is that it’s still evolving, moving forward, not backward.

Until 2002, when the government deregulated the media industry, there was only one state-run television station and a handful of heavily regulated radio outlets. Today, many of the licenses for the nearly 90 TV stations, 150 radio outlets and hundreds of newspapers are independently owned.

But media standards vary widely. Bribing reporters for favorable coverage is well-known, as are headlines based on rumors. Most large media outlets are funded by owners who don’t hide their strong political allegiances.

The media wing of Pakistan’s main intelligence service, the ISI, often exerts pressure on news outlets, according to former U.S. diplomatic and intelligence officials. It monitors the news, plants stories and intimidates reporters and editors.

The media wing’s larger goal is to keep the military’s influence on society obscured, its operations secret, and to promote its strategic interests, according to officials. This includes distancing itself publicly from the United States, even though its military has received billions in U.S. taxpayer money, records show.

Reports by Mir and other Pakistani journalists on the military’s secret support for the Afghan Taliban and the ISI’s involvement in CIA covert armed drone strikes deeply embarrassed the military establishment.

For a military that has directly controlled the levers of power three times in Pakistan’s history, these accountability stories only deepened its conviction to curb such journalism. International human rights investigations and U.S. State Department reports are filled with allegations of how hard it has tried since 2001.

In the Wild West province of Baluchistan, for example, security forces have been blamed by human rights advocates for the deaths and disappearances of many of the thousands of missing civilians. In that province, 13 journalists have been killed since 2008.

Mir produced more than 38 shows on the topic in the two years leading up to the attack on his life.

In 2012, a senior government official warned Mir to stop reporting on it: “Your life is under threat; you should stop raising your voice,” Mir quoted the man as saying.

Mir’s response: Another report on his show about Baluchistan’s missing.

In his father’s footsteps

Mir is the son of an outspoken newspaper journalist who died at age 48 under mysterious circumstances. Waris Mir had been feeling fine when all at once, one summer day in 1987, he fell ill. He was dead within a day.

During its war over Bangladesh’s independence in 1971, the Mirs resided on the campus of the University of Punjab in Lahore. His father, a professor there, entertained famous writers, politicians and actors.

The father was always on the side of peacemakers and underdogs. He hid Bengali students in the house when war broke out. His troubles intensified when military dictator Mohammed Zia-ul-Haq came to power. The father publicly opposed the general’s drive to turn secular Pakistan, with its majority Muslim population, into an Islamic state under authoritarian rule.

Waris Mir moved to London for several years to escape threats. When he returned to Pakistan, he wrote withering attacks against the Islamisation drive and the threats increased.

One morning, his father suddenly fell ill and died.

Family members saw his corpse blackening and suspected poisoning, which his father had openly worried about. But before a postmortem examination could be arranged, his father was buried.

Benazir Bhutto, who befriended the elder Mir in London but was not yet prime minister, came to the Mir house to console the family.

“What do you do?” she asked him.

“I play cricket,” said Hamid Mir, who was a rising sports star.

“No, you should become a journalist like your father,” she said.

Bruised but determined

Two months later, Mir started his reporting career in Lahore as an intern, earning $15 a month. He was good at building sources and fit comfortably into the political circles where the scoops were to be found.

At 24, he got a big one. Pakistan’s president, Ghulam Ishaq Khan, was planning to dismiss the Bhutto government. He typed furiously.

Within an hour of filing the story, he was in trouble.

He was abducted, beaten and driven to a house where his captors demanded to know his source for the story.

“Who gave you that story!?” one demanded.

His source was confidential, he said.

“Who!!!?”

They held his arms and started to take off his shirt.

“I tried to be strong,” he said. “But when they removed my clothes, I broke.”

He told them that his source was the minister of parliamentary affairs. They put him back in the car and dumped him along the road.

The bruised Mir said he hoped his mother would ask him to quit journalism. “Your father also faced a lot of problems, but you have to be determined and committed,” she told him.

He returned to work. Within a few years, he was the go-to reporter at the Daily Jang. Mir was one of the first Pakistani journalists to interview Nelson Mandela, president of South Africa.

“It became very difficult for me to control my emotions because I wanted to hug him,” Mir said about Mandela. Next came interviews with Osama bin Laden, Tony Blair and Hillary Rodham Clinton.

In 2002, he joined Geo, the up-and-coming television station. His popularity soared as Geo grew into one of the most-watched networks in the country.

Presidents, ambassadors and ministers sought to be on Mir’s “Capital Talk,” a four- nights-a-week news talk show that mixed traditional reporting with opinion. What he said mattered. He moved people to protest. He stirred debates on the touchiest subjects.

“Pakistan is a highly politicized society. . . . So there are people who are his real fans in the country and there are people who regard him as sensationalist and are his opponents,” said Zaffar Abbas, editor of Dawn, one of the country’s oldest newspapers.

“He has been a controversial person in the eyes of the government, in the eyes of the security establishment, in the eyes of many other people in Pakistan.”

Marked for death

One of Mir’s guests on “Capital Talk” in 2009 was 11-year-old Malala Yousafzai.

The young schoolgirl reminded Mir, he said, of the strong female leaders his father had befriended and defended. On the show, she calmly defied the armed Pakistani Taliban who occupied her isolated Swat Valley.

In 2012, the Taliban shot her in the head as she and her classmates rode in a school van. Mir said he felt as if someone had attacked his young daughter.

That night he exploded on camera: “I have a question for those who attacked her! . . . The question is whether you think that after shooting an unarmed and innocent school-going girl you have the right to call yourself a Muslim?”

The reaction to his support for Malala was not universal adoration. Death threats poured in by e-mail, Twitter and phone calls.

He said he realized the depth of his troubles when a police officer sent to protect him at a rally spat at his feet. “Why would you defend Malala?” the man growled. “She is the daughter of a whore.”

Several weeks later, a neighbor’s driver spotted an explosive device hidden in the undercarriage of Mir’s car outside his home. A bomb squad defused it. The Pakistani Taliban claimed responsibility, as they had for shooting Malala. A war against Hamid Mir had begun. He scrambled to defend his life and that of his wife and children.

Mir rented a second house, then an apartment and kept the locations a secret. He moved his family every few days.

The people closest to him, he said, pleaded for him to leave the country.

Backlash from the government

Two weeks before the attempt by gunmen on Mir’s life, an ISI official beckoned him to come to the Serena Hotel in Islamabad, he said.

There, according to Mir’s affidavit, a senior official “pleaded with me” to stop reporting on the Army and the prosecution of former president Pervez Musharraf. He is accused of abrogating the constitution when he declared a state of emergency for six weeks in 2007. Mir had done 44 reports on the issue.

“If the Army stops interfering in politics, then I will never do a program on it again,” he told the man from the ISI, the affidavit says.

The next week, ISI officers came to his home, Mir said. His name was on a hit list, they told him. He told them that he was more worried about them, the ISI.

The evening of the shooting, Mir said he spoke with his wife by telephone. He told her that he didn’t want to travel to Karachi but needed to broadcast a show from the city.

Later that evening as he left the airport, a gunman opened fire as his car slowed to round a corner. His driver sped away. Mir felt additional shots strike him and realized that gunmen on motorcycles had given chase.

“Run away! Run away!” Mir said he told the driver. Then he called his producer on the telephone: “I am under attack. I don’t know where to go.”

The gunmen pursued Mir’s car for 15 minutes, shooting as they gave chase, until his driver pulled into the Aga Khan University Hospital. The motorcycles disappeared into traffic.

At the hospital, Mir, unconscious, was hooked to monitors and blood bags. The nation was riveted. Would he survive? Should he survive?

Some called him a hero; others labeled him a traitor, a Jew, an agent of India and a CIA spy.

When he awoke two days later, the prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, brought flowers and an assurance: A commission would be created to find the culprits. It has yet to publish its findings.

Weeks later, when Mir was strong enough, he wrote the affidavit, providing investigators the names of people who had threatened him and what they said.

He hadn’t seen the people who shot him, he wrote, but “I suspected that some elements from the ISI were behind the attack.” He recounted for investigators that senior ISI officers had confronted him about his reporting nearly a dozen times.

The assassination attempt had to be ISI-directed, he told investigators. That same day, former president Musharraf was in Karachi, too. The city was on high alert to protect him.

“Only they can manage that the CCTV cameras were not working. And only they could have known about my travel plans,” he wrote.

The Pakistan government “is doing its level best to provide security to journalists,” said Nadeem Hotiana, embassy spokesman, including providing protection to journalists upon request. “The government has intensified efforts to apprehend all criminals involved in such attacks on journalists.” He declined to comment on behalf of the ISI. In the past, the ISI has said it had no involvement in Mir’s assault.

Before Mir was strong enough to get out of bed, his brother appeared on Geo and publicly accused ISI chief Lt. Gen. Zaheer ul-Islam for being behind the attack. It was a miscalculation of major proportions.

Nationalistic fanatics called Mir and Geo traitors. The ISI was furious. In a statement, it accused Geo of trying to weaken Pakistan. Geo officials apologized in a newspaper advertisement, but when the pressure against the network continued, it sued the intelligence agency. The suit, which is pending, claimed the ISI had wrongly accused the channel of being “anti-Pakistan” and of inciting violence against it.

Mir said the hospital soon asked him, still weak and bedridden, to leave. He was moved to the nearby Marriott hotel, where a room with hospital equipment was set up.

Geo, however, had nowhere to seek refuge. Programming in some cities was blacked out or moved to obscure channels when the government suspended their broadcasting licenses. Many advertisers were intimidated from doing business with Geo.

“The attack absolutely changed everything … We disappeared, became another missing person,” said Imran Aslam, president of Geo.

A life in hiding

Mir went back to work only three months after the shooting. He was still on pain medication. “If the Titanic sinks, I want to go down with it,” he told those who said he should leave the country.

Mir realized his life had changed dramatically. Just a few years ago, he would take evening walks in the park and often buy fresh juice before his show.

He can no longer walk anywhere alone. Other journalists at Geo do much of his reporting because meeting sources is almost impossible, except by phone, which he assumes is monitored.

Mir said he has toned down his criticism of military courts and other issues. He rarely reports anymore on Balochistan.

“Survive, then do [journalism],” is his motto now.

His only escapes are trips overseas. Several months ago, he went out to dinner in Dubai with his wife. “It was like a prisoner came out of prison,” he said, cracking a rare smile.

He has sent his children out of the country. He said his wife is angry that he has not left.

Large, yellow concrete barriers fortify the outside of one of his homes on the outskirts of Islamabad. Three guards and barbed wire are conspicuous at what otherwise appears to be a typical middle-class house. The traditional candy and nut bowl is covered in plastic wrap, a sign he’s not usually here.

When Mir travels by car these days, he waits by the front door of his home for his driver to start the vehicle. Once he hears the motor running, he dashes into the back seat, behind tinted window shades.

Twenty minutes later, after Mir’s car passes around the barricades of Geo’s headquarters and through the security gate manned by three guards, does he finally relax. He is eager to get to work.

“He’s out there reporting, covering things that no one else is covering, saying things that no one else is saying. . . . It would be devastating if he were in a position where he had to leave,” said Joel Simon, executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Some believe Mir is motivated by money and fame. Others believe he is driven by a need to defend his colleagues.

“If I leave the country, a lot of young journalists, they will be discouraged,” Mir said he tells his children.

Lingering pain

In his office at Geo on a recent morning, Mir looks over at a row of small televisions.

“What should we do the show on?” his producer asks.

They settle on upcoming elections and the gasoline crisis.

As he reads news clips, his production team books guests, writes scripts and creates video pieces. “Nazish, give me the shots of the minister making promises,” Mir calls out as he walks into the production room.

By 6:15 p.m., Mir is tugging at his left leg and stuffing his chair with extra cushions and stretching. His leg, when it’s not numb, burns in pain from the bullet still lodged in it. A second round is stuck in his lower stomach, and the fragments of a third are near his bladder.

But when the night’s guests begin to arrive — the petroleum minister and a former finance minister — Mir morphs into the focused, charming television star. “I’m going to ask questions” that will leave him “shaking,” he jokes with one guest about another.

At 8:05, he stares straight into the camera: “Bismillah Arrahman Arrahim, Asalamalaikum! Welcome to ‘Capital Talk’!”

Mir barks tough questions. When one guest says the oil shortage is proof that a military takeover is the only way to save the country, Mir lights up. “Martial law has never solved any crisis in Pakistan!” he roars.

During a break, the petroleum minister chuckles: “I don’t usually come on TV. But you have a way of taking information [from] me.”

At 8:55, the show ends. Mir escorts his guests to the elevator, laughing and back- slapping until the doors close.

Then, he huddles with his staff and thinks to himself, “Who have I hurt?” He rushes downstairs.

The answer portends the next round of threats. He inspects the dark parking lot and dashes to the waiting car. Two uniformed, armed guards climb into a second security vehicle. Mir zooms out into the night.

Campaign

About this Site

Pressuncuffed.org seeks to encourage and promote rigorous student reporting, scholarly research and debate on the role of, and obstacles to, independent journalism in the United States and abroad. Our website features reporting by University of Maryland students about press freedom in the United States and abroad. It also offers resources to instructors elsewhere who may want to teach classes or hold workshops on this theme. In the near future, this site will become a place for student work from around the country and abroad.

Dana Priest, two-time Pulitzer Prize winner at The Washington Post and Knight Chair in Public Affairs Journalism at the University of Maryland.